57. Left over from last week's session:

assignments 55(b) & 56.

58. Read the three new texts and bring your notes.

We will discuss your questions and remarks in class.

– "Can a logographic script be simplified?"

59. We will discuss this article first, on a page-by-page basis, and on the basis of your remarks.

– "The failed assault on Chinese characters"

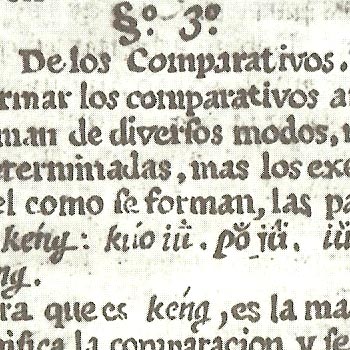

60. On p. 75 of Kraus' text, he notes the Korean use of "a more clearly phonetic" script instead of characters.

a. What is the name of this script? How and when did it come into being?

b. How "clearly phonetic" is it?

c. If the Chinese script is not "clearly phonetic", then how could it best be characterized?

d. The phonetic nature of the native Korean script have engendered some enthousiasm about its qualities among linguists and educators.*)

For an example, see "In praise of: The world's best writing system, which states:

"it turns out that different writing systems are not all equally well equipped to capture the full range of a language’s grammar".

Give a concrete example of one grammatical feature, in a language of your choice, plus a writing system unequipped to capture that feature.

_____

_____

*) Apart from Korea's script, its language has likewise received distinguished praise, albeit by non-linguists, e.g. "Korean is, as a matter of fact, a very good language" in Kim Il Sung, "Problems related to the development of the Korean language", Works, Volume 18: January - December 1964, Pyongyang, Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1984, p. 17. (in BB "Course Documents")

61. Kraus' chapter repeatedly mentions John DeFrancis' work.

a. If you are not familiar with John DeFrancis' name:

do look up some details about his life and work.

b. On p. 78, Kraus states that "DeFrancis points out that..." without quoting a source.

Can you trace this citation?

c. Kraus paraphrases DeFrancis' statement that in the 1950s, "no one in China was willing to appear to challenge Stalin on this point".

On what point, exactly?

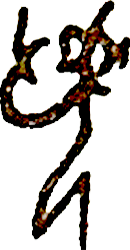

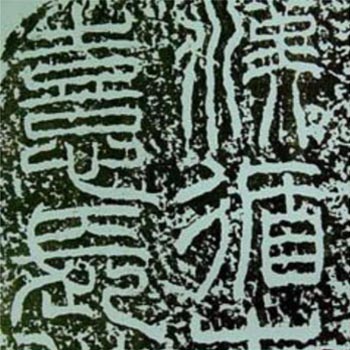

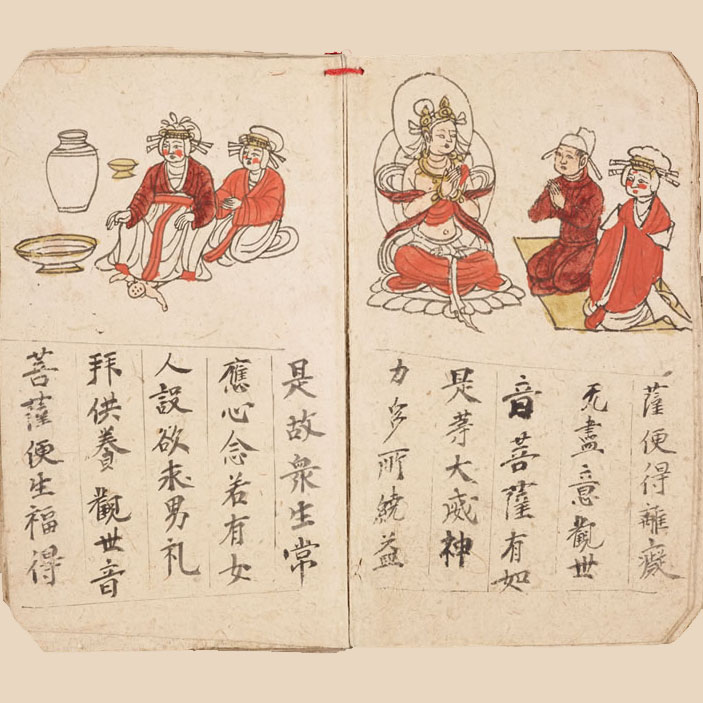

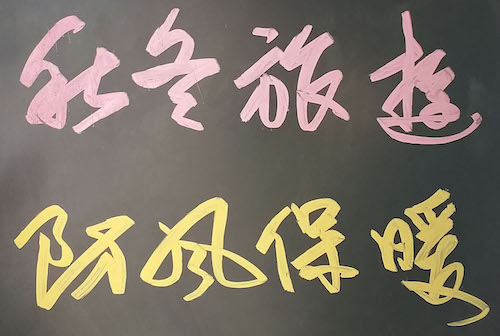

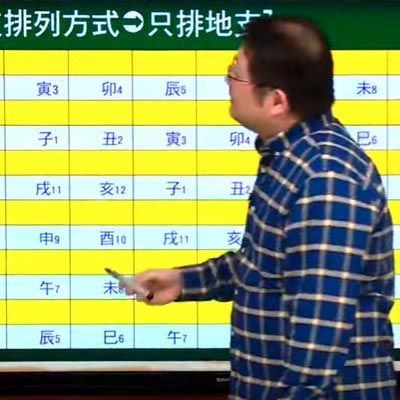

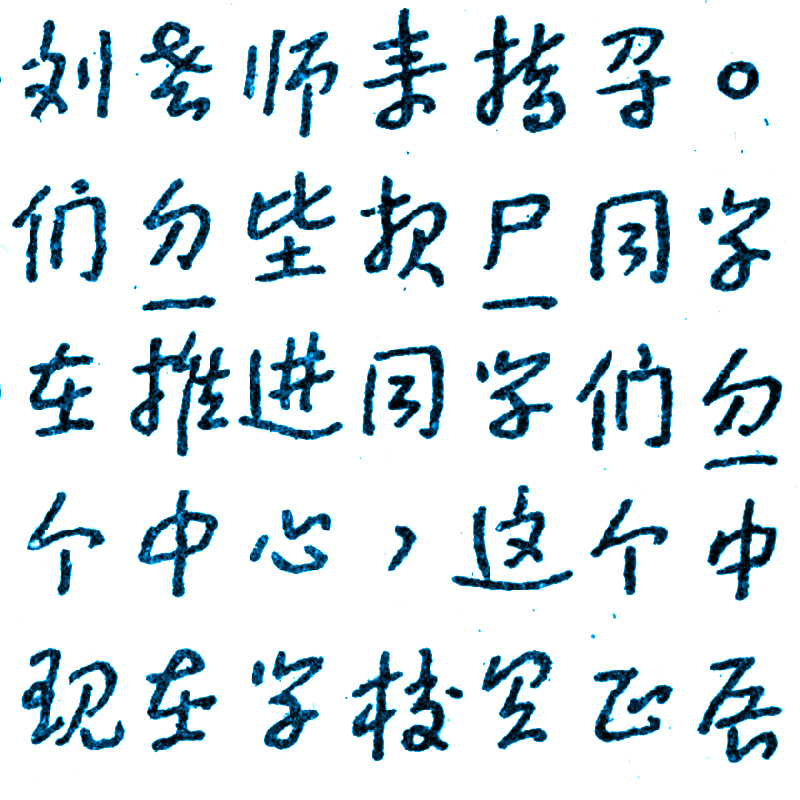

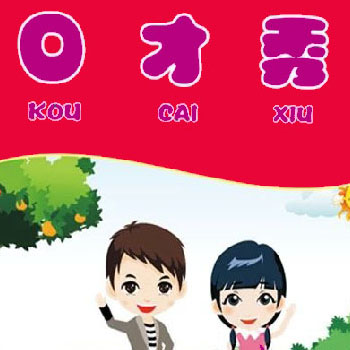

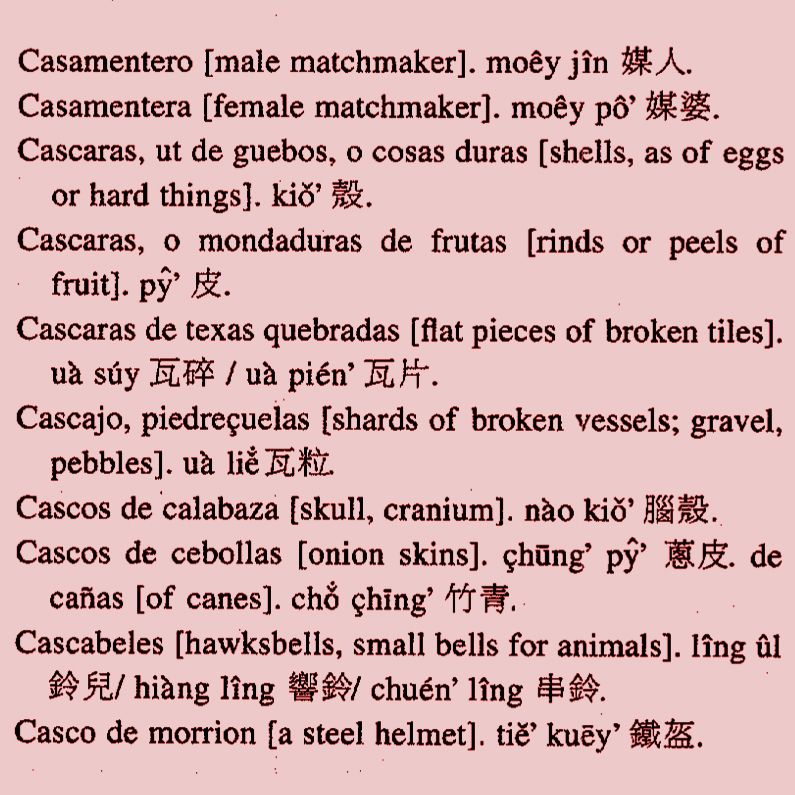

62. P. 81 shows a woodcut from a 1958 issue of the journal 中国妇女 Zhōngguó Fùnǚ "Women of China".

a. Can you identify the characters in this illustration?

b. Can you translate them? ( A friendly reminder: prepare all your answers in writing)

A friendly reminder: prepare all your answers in writing)

63. On p. 82, Kraus mentions a childhood memory from Chinese opera singer 新凤霞 Xīn Fèngxiá (1927-1998) featuring a "discarded cap of a fountain pen".

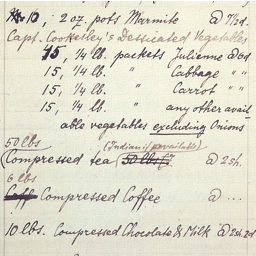

a. When and where were fountain pens invented? What writing tool(s) where they meant to replace or supplement?

b. When were they first used in China? What writing tool(s) did they replace, or supplement?

– "Features of the Chinese script"

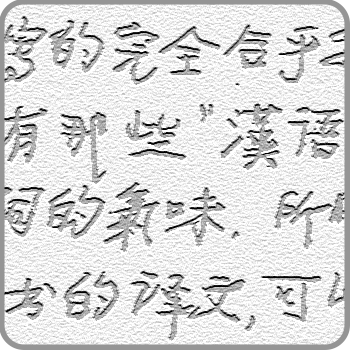

64. The first paragraph of p. 365 describes what characters "consist of".

What consequences can this phrase "consist of" have in terms of linguistic methodology?

65. For each of the stroke-order principles in Table 12.5, try to find at least one exception.

66. For native speakers of Mandarin:

in Table 12.10, compare these letter names with your own pronunciation, and note down any differences.

67. In Table 12.11, can you think of punctuation marks which are missing?

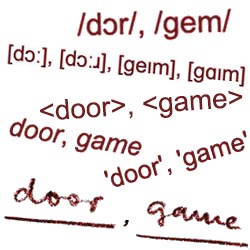

68. At the bottom of page 371, what do the slashes transcribe in "the sound /s/"?

Can you write these three examples – cent, sent and scent – using the same transcription?

69. At the bottom of p. 372, please comment on the English translation "A book from the sky".

70. The small text of p. 375, mentions a "danger of circularity".

Please formulate this danger in two or three sentences of your own.

71. Some historical aspects of the character 年 are mentioned on p. 377.

What linguistic terminology is available to describe the relationship between 'millet', 'harvest' and 'year' discussed here?

72. Section 12.3.3 discusses the 六書 liù shū 'Six Categories of the Script'.

In his 2009 "Ludic writing" article, Wolfgang Behr proposes a highly original model for the analysis of the relationship written characters and linguistic signs.

This model, in his words (2009: 291)

"allows us to identify certain character structures beyond the coverage by the traditional “six scripts” (liùshū 六書) theory of the Hàn dynasty, [...] whose inadequacies have long been noted and discussed."

Can you give concrete examples (quoting individual characters) of such "inadequacies"?

73. Table 12.14 illustrates the large propertion of infrequent characters.

Can you identify one or more social factors which have contributed to the survival of infrequent characters?

Leiden University's measures against the spread of the COVID-19 virus

Leiden University's measures against the spread of the COVID-19 virus  Intro / Speaking and writing in China

Intro / Speaking and writing in China Texts

Texts

Fig02.jpg)

title page red.jpg) Texts

Texts

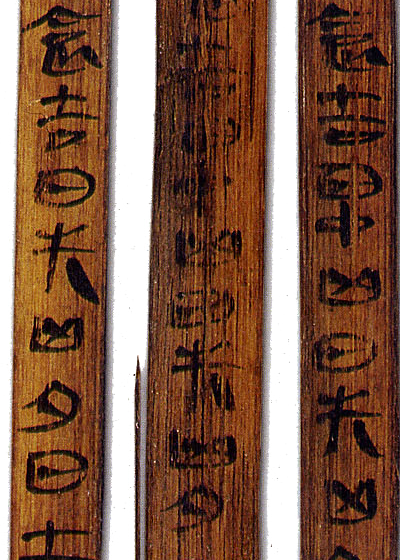

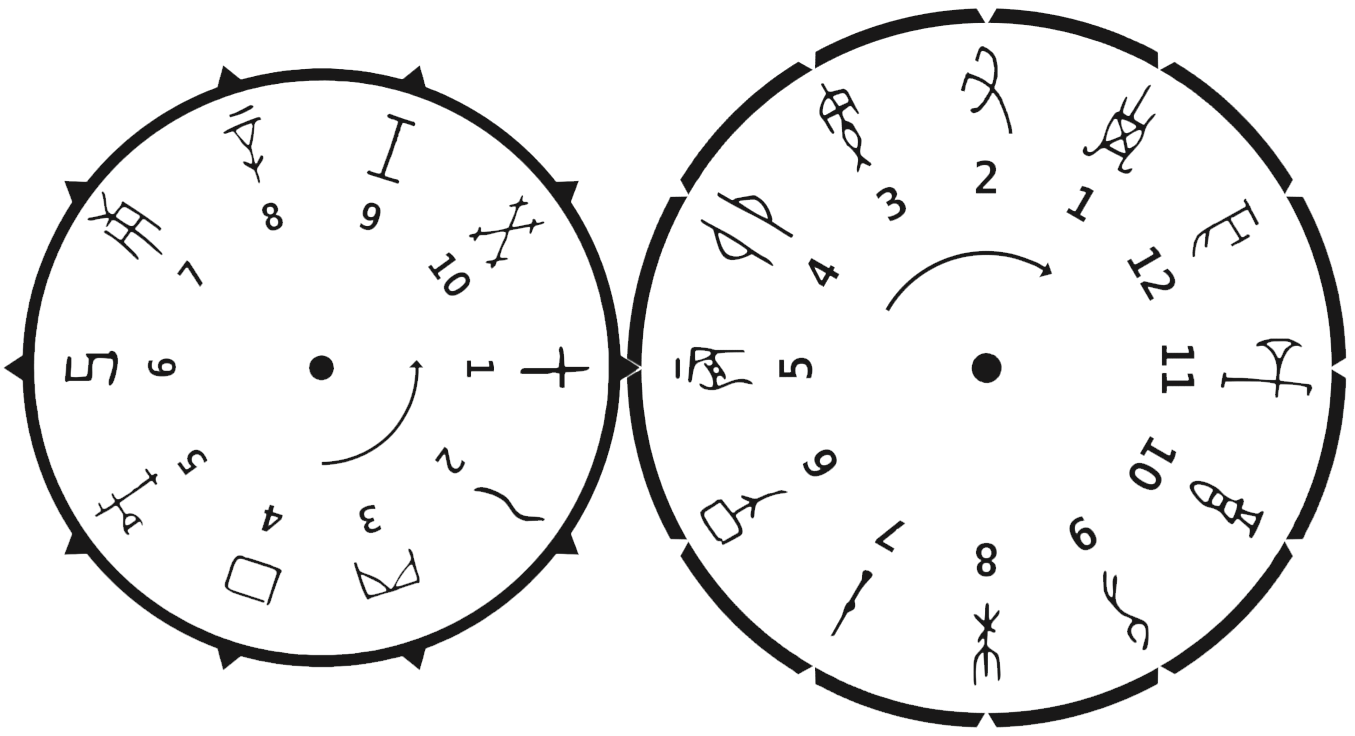

Corresponding with Heaven: The early scribes

Corresponding with Heaven: The early scribes

Texts

Texts

Encore special:

Encore special: