Sessions

Block 3

Intro / Speaking and writing in China

Intro / Speaking and writing in China

Writing is – in most definitions – connected with language. But if language travels through sound waves and writing is a visual medium, then how do these two domains interact?

Writing systems displays intricate and diverse ways of mapping the sounds and meanings of language to a visual format.

Once written down, some elements from speech are preserved and some are lost. And vice versa: the visual signal may transmit components from the spoken original, but also features which are absent in spoken form.

In this first session, we will explore how language comes to us through the Chinese script – and how fast such modes can change.

Texts

Texts

-

Chao (1980)

趙元任 Yuen Ren Chao, 序 "Xù" [Preface]

In: 趙元任 Yuen Ren Chao, 中國話的文法 Zhōngguóhuà de wénfǎ [A grammar of spoken Chinese].

香港 Hong Kong: 中文大學出版社 Chinese University Press, 1980, frontispiece.

Translation of Yuen Ren Chao, A grammar of spoken Chinese.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 1968. Translated by 丁邦新 Pang-Hsin Ting.

Chao's 序 will be handed out and introduced in class. No preparation is needed for this text.

Chao's 序 will be handed out and introduced in class. No preparation is needed for this text.

-

Norman (1988)

"The Chinese script"

In: Jerry Norman, Chinese.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988, Chapter 3 = pp. 58-82.

Norman's work is available from the Asian Library, on the linguistics handbooks shelves.

Highly recommended: a "must-read" classic. This book is widely available and inexpensive.

– In short: get your own copy!

Study suggestions

Time management: do not underestimate assignment #5 below. It may involve more reference checking than would seem at first glance.

Assignments

![]() Please make sure you prepare your answers to all questions & assignments in writing.

Please make sure you prepare your answers to all questions & assignments in writing.

1. Read the assigned chapter from Jerry Norman's Chinese.

In preparing this text, please check that you are familiar with

Note down any difficulties you may have in reading the text, and bring your notes to class.

technical terms in English and in Mandarin (including the corresponding Chinese characters);

names and dates for dynasties, historical periods and historical figures;

geographical designations.

2. On p. 58, the origins of Chinese characters are outlined.

a. In English, do you know a term for the study of writing systems? And in Mandarin?

b. Can you name (at least) three families of scripts, i.e. writing systems of the world which (as far as we know) developed independently?

c. Is the oracle bone script the undisputed precursor of the modern Chinese character script?

d. Can you name (at least) seven different Sinitic languages?

Please give the English and in Mandarin names for each of these, as well as the Chinese characters (简体 & 繁體) for each name.

e. What is the oldest Sinitic phase which has been reconstructed in phonological detail? Please give (approximate) dates.

f. Is the language encoded by the oracle bone script the undisputed precursor of the modern Sinitic languages?

3. The ideographic notion, i.e. the notion "that Chinese characters in some platonic fashion directly represent ideas rather than specific Chinese words" may be "patently absurd" (pp. 60-61), but it is immensely popular nonetheless.

Find a reference (in print or online) which clearly demonstrates, or is clearly based on, the ideographic notion.

a. From this source, note down one specific statement or claim demonstrating this notion.

b. Formulate a counter-argument against this specific statement or claim, basing yourself (at least in part) on the information in section 3.1.

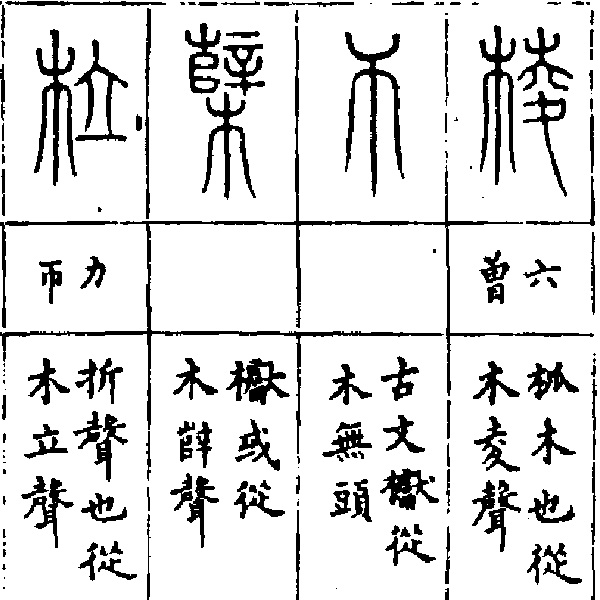

4. Pages 67-69 introduce the 說文解字.

In one or two sentences, summarize the significance of this work

for the study of the Chinese script; and

for Chinese lexicography.

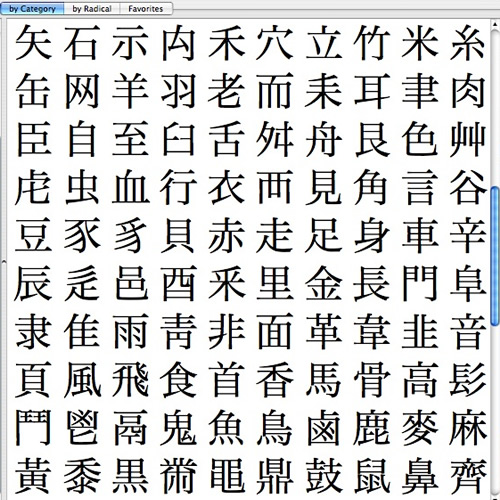

5. On p. 76, please study Table 3.6 carefully, including the notes on p. 77.

a. Can you read all characters listed in the Table?

For your reference: see e.g. 國際電腦漢字及異體字知識庫 / International Encoded Han Character and Variants Database.

b. Can you give more recent examples of individual characters created in order to "adapt[..] the traditional script to the modern language" (p. 75)?

6. In note 8 of p. 81, please define the term homophonous in your own words.

7. In note 10 of p. 82, it is noted that "the alternation of words beginning with sh and r in a single phonetic series is unusual".

Find another example of this unusual type of alternation in the traditional character script.

8. In the same note 10, consider the example of ràng 'to allow' again.

Note that "ràng" is italicized, but " 'to allow' " is placed within single quotation marks.

a. In your own words, formulate the difference between these typographical conventions.

Which linguistic units do they represent?

b. Can you list other typographical conventions, representing other linguistic units?

For each unit, give English and Mandarin names, as well as the Chinese characters (简体 & 繁體).

c. Is there also a typographical convention which represents items as orthographic units, i.e. as the written forms of a script?

Corresponding with Heaven: The early scribes

Corresponding with Heaven: The early scribes

At the dawn of history, humans were fully modern in the anatomical and in the neurological sense. Their brains, and their languages, were as complex and as diverse as they are today. There were just fewer speakers.

Even at this early stage, the world must have been teeming with linguists. We know nothing about their theories, but their legacy remains with us today, for they created the first writing systems.

The art of writing was invented more than once, and the puzzle how to represent sound and meaning in graphs has been solved in very different ways. The Chinese case offers us a rare insight in the tenacity of some cultural artefacts.

This week, we will:

study the material culture which produced a script whose characteristics have survived into the digital age;

consider the challenges of interdisciplinary studies; and

learn how to introduce a text dating back more than three millennia to a modern audience.

|

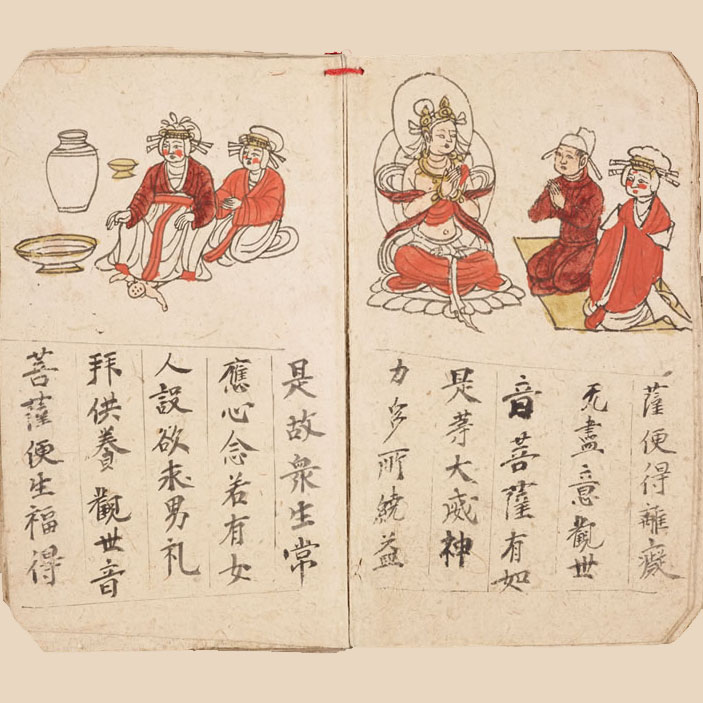

Click left \ right to enlarge Source: Lindqvist, China: Empire of living symbols (2008) |

Texts

-

Keightley (1985)

-

Preamble ["Puk!"]

-

Chapter 1, "Shang divination procedures"

-

Chapter 2, "The divination inscriptions"

David N. Keightley, Sources of Shang history: The oracle-bone inscriptions of bronze age China.

First edition 1978; paperback edition, with corrections, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985.

Pp. 1-2 (Preamble), 3-27 (Chapter 1), 28-56 (Chapter 2).

For Chapters 1 and 2, your reading assignment does not include the copious footnotes (which take up >50% of the text).

For Chapters 1 and 2, your reading assignment does not include the copious footnotes (which take up >50% of the text). Available in the Leiden Asian Library: see the dedicated Course Shelf, number ALCOL17-60, for this course.

-

-

Lǐ (1989)

"月㞢食"

李圃 Lí Pǔ, selection and commentary, 甲骨文選注 Jiágǔwén xuǎn zhù [Oracle bone writing: An annotated anthology].

上海 Shanghai: 古籍出版社 Gǔjí Chūbǎnshè, 1989,

Section 1, pp. 1-8.

Available in the Leiden Asian Library: see the dedicated Course Shelf, number ALCOL17-60, for this course.

Background

Background

-

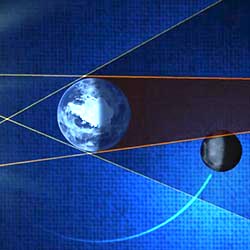

NASA (2011)

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, "Lunar eclipse essentials"

Uploaded to Youtube on 8 June 2011.

-

Djamouri (1992)

Redouane Djamouri, "Un emploi particulier de you (有) en chinois archaïque"

Cahiers de Linguistique Asie Orientale, January 1992, Volume 21(2), pp. 231-289.

A PDF of this article is also available online at Persée.

-

Thurston (1994)

Hugh Thurston, "The Chinese"

In: Hugh Thurston, Early astronomy. New York: Springer, 1994, pp. 84-109.

Leiden University Library code: GORLAE ASTRON QB016 203.

Reading notes

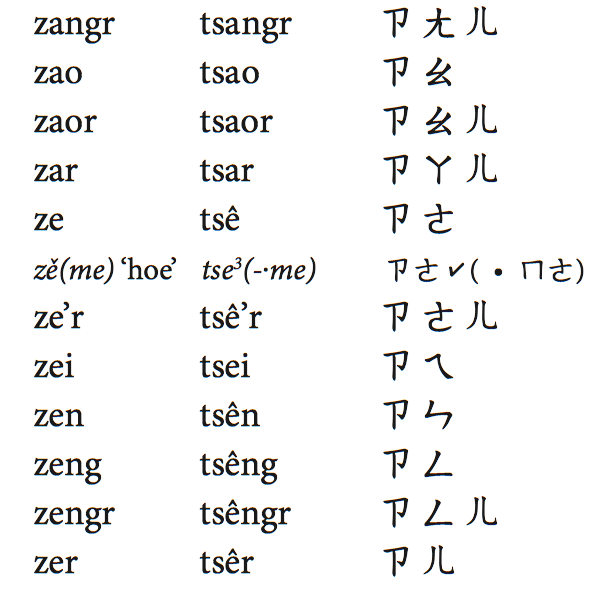

9. In case you need help with the Wade-Giles spelling:

– for systematic guidelines & conversion, see Appendix D in A grammar of Mandarin; or

– for ad-hoc conversion, see e.g. the Chinese Text Project's transcription-conversion tool.

10. In case you need help with the sexagenary cycle:

– for systematic guidelines & conversion, see Tables 9.3 & 9.4 in A grammar of Mandarin; or

– for ad-hoc conversion, see e.g. Wikipedia's Stem, Branch and Stem-Branch tables.

11. "Wu Ting's reign" (Keightley 1985: 1):

Wikipedia has a list of Shang Kings.

Assignments

12. Individual items

Biyue, Jiayun: Your backlog assignments for week 1 are due this Friday, 9 Feb 15, at 1:00pm.

Please note the format requirements for written assignments.

The assignments for this week's session are below.

A friendly reminder: make sure to prepare all your answers in writing, in English!

– Keightley (1985):

13. Read the assigned texts from David Keightley's Sources.

In preparing this text, please check that you are familiar with

- technical terms in English and in Mandarin, including the corresponding Chinese characters,

– e.g. "hsin-wei, eighth day of the week";- names and dates for dynasties, historical periods and historical figures

– e.g. "Wu Ting";

- geographical designations

– e.g. "the powerful Ho".

For hints and suggestions, please consult the Reading notes.

Note down any difficulties you may have in reading the text, and bring your notes to class.

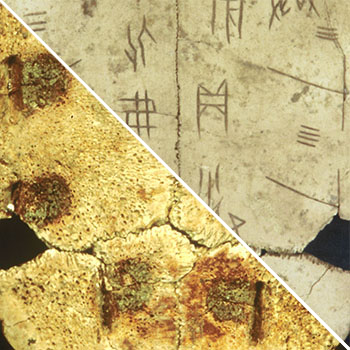

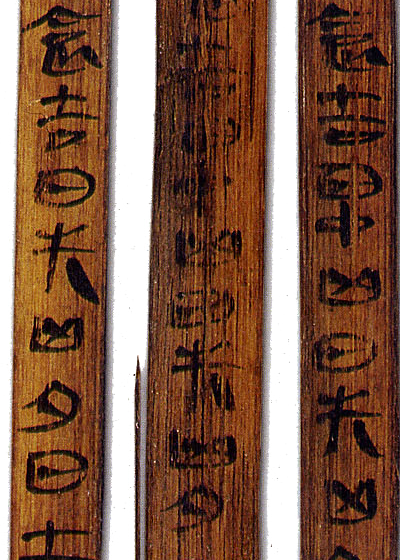

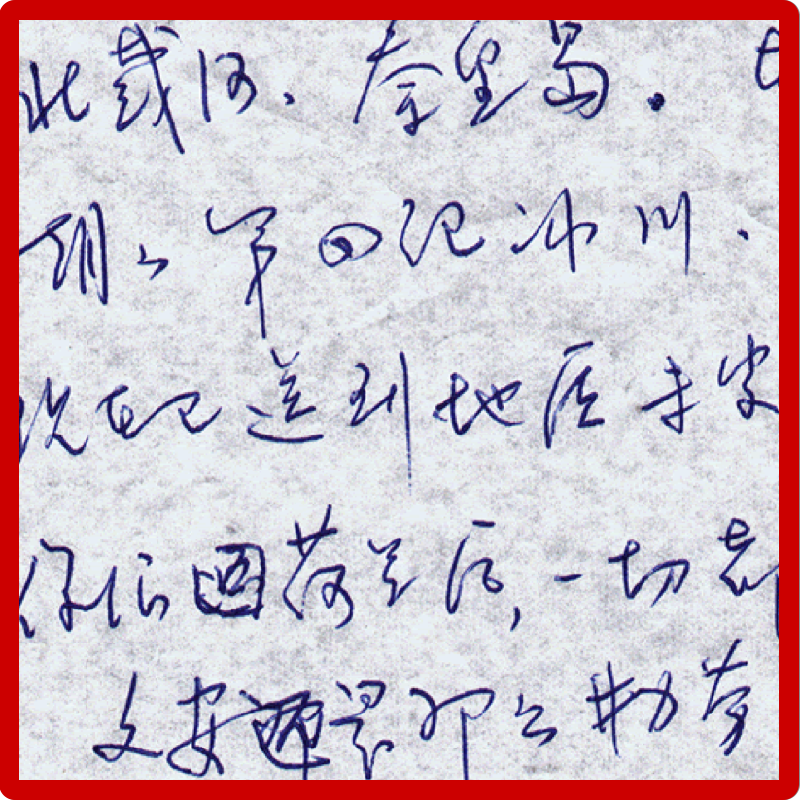

14. In the illustration above, the left bottom half shows the inner side of an oracle bone, and the top right half shows the outer surface of the same shell.

Either half is clickable to show a full view.

In these photos, please identify the "series of hollows" (Keightley 1985: 18) and "the characteristic pu 卜-shaped crack" (ibid.).

15. On p. 50, it is explained that "[a]s a rule, the inscriptions appear to have been carved above, or to the side of, the pu cracks and on the side of the crack which lacked the transverse branch".

Can you confirm this general rule for our "月㞢食" text?

– Lǐ (1989):

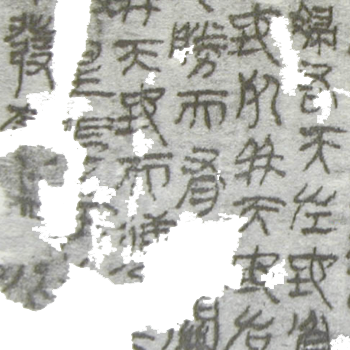

16. On the basis of 李圃 Lí Pǔ's helpful notes, read and prepare an English translation of the oracle bone text "月㞢食".

Please note down any difficulties encountered in Lǐ's commentary.

17. Oracular text, line 4, character 2:

In your own words, define the relationship between the character 㞢 and the character 有.

You should minimally formulate what you know on the basis of Pǔ's comments, combined with your own experience.

In this connection, also compare the comments on character adaptations from our first session.

For more background, you may consult Djamouri (1992).

Language and script (1): Writing Chinese sounds

Language and script (1): Writing Chinese sounds

Language is all about sounds and meanings, and linguistics has well-established traditions for the written documentation of auditory as well as semantic details. Today's subject is the auditory domain, which comprises phonetics as well as phonology.

We will take a hands-on approach, going through various principles while applying these to examples from Chinese languages.

Today's session will consist of three parts:

- Last week's round-up:

Concluding the discussion of our oracle-bone session

- Phonetics recap:

Overview, guidance & hints, plus "everything-you-wanted-to-know-about-phonetics-but-where-afraid-to-ask" opportunities

- Linguistic transcription:

Distinguishing between phonetic and phonological notations, with examples & exercises

Texts

Texts

-

IPA Charts

from the International Phonetic Association:

-

All offical charts are on the IPA website

-

Pat Keating has an IPA Chart with sound & video

-

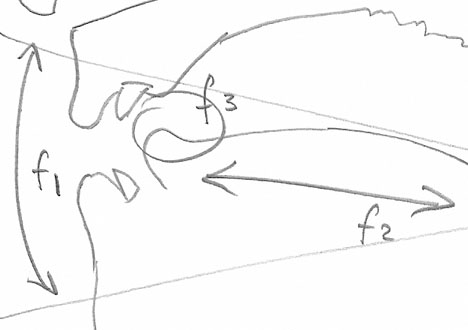

"Formants"

See <formants.png>

-

"An introduction to linguistic transcription"

-

De Saussure (1916)

De Saussure (1916)

"Nature of the linguistic sign"

In: Ferdinand de Saussure, Course in general linguistics.

New York: Philosophical Library, 1959.

Translated from the French [Cours de linguistique générale, original edition 1916] by Wade Baskin.

Chapter 1, pp. 65-70.

-

Wiedenhof (2015)

"Phonology"

In: Jeroen Wiedenhof, A grammar of Mandarin.

Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2015.

§ 2.8, pp. 53-55

Assignments

Hand-in Assignment #1

Imagine that:

- the five fragments pieced together to form last week's oracle bone were shown in a museum exhibition, and

- you were asked to write the accompanying object label, intended for an English-speaking museum audience.

On the basis of your work for last week's assignments, prepare a text which could serve as that object label. This text should minimally include:

- information about the age and the provenance of the object;

- short remarks about the type of text, and the language of the inscription;

- a full translation of the "月㞢食" text.

Hand in your work, printed on paper, at the beginning of class on 19 February, or in my pigeonhole beforehand.

Please note the format requirements.

Small is beautiful: maximally one page (A4).

18. Individual items

Nick: Your backlog assignments for week 2 (items 13 thru 17) are due this Friday, 16 Feb, at 1:00pm.

Please note the format requirements for written assignments.

– Last week's round-up:

19. At the start of this this session, let's finish our discussion of the oracle-bone items.

Please check your notes and bring any unanswered issues to class.

– Phonetics recap:

20. A short overview will be presented in class.

Please prepare yourself by consulting all relevant materials:

- the IPA chart, especially the three sections labelled

- "Consonants (pulmonic)",

- "Vowels", and

- "Tones and word accents"

- the info sheet on vowel Formants

In all cases, please try to figure out the general structure and design of the system.

Make sure to note down any problems you encounter, and bring these to class.

– Linguistic transcription:

21. Read (Sections 1-3) of the assigned "Introduction to linguistic transcription" and note down any questions or difficulties in this text.

Under Section 5, re-write sentences 1 to 10 in a linguistically consistent transcription.

22. Read the assigned texts from De Saussure (1916) and Wiedenhof (2015).

Note down any questions or difficulties you run into, and bring your notes to class.

We will discuss your questions and remarks on a page-by-page basis.

In case you need to check, here are some references to the Saussurean originals for your convenience.

23. Now formulate in your own words what constitutes the division of labor between phonetics and phonology.

Two or three sentences will suffice, but you need to use at least two original examples in a languages (or languages) of your choice.

Please pay special attention to the way your transcribe these examples.

...and the encore

24. Complete the table:

Language

Semantics

'Good shot!'

Phonetics

Phonology

Morphology

Syntax

Script

Chinese characters

好球!

Pinyin

Character Pinyin (CP)

Linguistic Pinyin (LP)

Wade-Giles

Yale

Bopomofo

...

...

...

Doing right by a script: The tools of lexicography

Doing right by a script: The tools of lexicography

In week 2, we saw how the invention of writing was embedded in technological and economic change.

Today, we will explore early advances in Chinese lexicography against the backdrop of philosophical and political developments In Qín 秦 and Hàn 漢 times.

This session will consist of three parts:

- Last week's round-up:

Concluding our transcription session

- This weeks' centerpiece:

An unconventional look at the establishment of writing conventions

- Looking ahead:

Exploring possibilities for you term paper

Texts

-

Galambos (2006)

Galambos (2006) -

"Shuowen Jiezi"

Chapter Two, "The Qin and Han creation of the standard"

Imre Galambos, Orthography of early Chinese writing: Evidence from newly excavated manuscripts, pp. 31-63.

Budapest: Eötvös Loránd University, Department of East Asian Studies, 2006.

A PDF of this book is available online on Imre Galambos' page

....or use the direct link to this title.

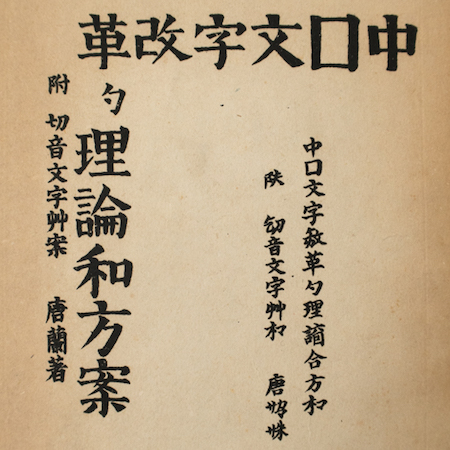

From Wikipedia: The free encyclopedia

|

Source: Archive.org |

-

許 Xǔ (100)

許慎 Xǔ Shèn, 說文解字 Shuō wén jiě zì [Discussion of simple characters and analysis of complex characters]

Edition: 说文解字: 附检字 Shuō wén jiě zì: Fù jiǎn zì [Discussion of simple characters and analysis of complex characters: With a character index].

北京 Peking: 中華書局 Zhōnghuá shūjú, 1963.

East Asian Library number: SINOL. 5093

Available in the Leiden Asian Library: see the Course Shelf dedicated to this course, number ALCOL17-60.

Assignments

25. Individual items

Wenjing: Your backlog assignments for week 2 (##12-17) are due this Friday, 23 Feb 15, at 2:00pm.

Chengcheng: Your backlog assignments for week 3 (##21-23) are due this Friday, 23 Feb 15, at 2:00pm.

Please note the format requirements for written assignments.

– Last week's round-up:

26. Left over from last week: discussion of assignment 21.

Please check your notes and bring any unanswered issues to class.

27. Have another look at last week's encore.

As discussed, we will checking back on this table over the following weeks.

For now,

- please fill at least four blanks of your choice in the last column

- see if you would like to add any items in the first column

– This week's centerpiece:

28. Read the first two texts:

- Galambos' Chapter Two, "The Qin and Han creation of the standard" and

- the Wikipedia article "Shuowen Jiezi".

Note down any difficulties you may encounter in these two texts, and bring your notes to class.

We will discuss your questions and remarks on a page-by-page basis.

29. The third title is a modern reprint of the 說文解字 Shuō wén jiě zì.

(a) Have a good look at this book, which is currently available from the course reserve shelves in the Leiden Asian Library.

(b) Check that you understand how the work is organised.

(c) Find the characters

,

,

and

in this dictionary.

For each of these four characters, write down

- the page number for the entry in this modern edition

- the Shuō wén jiě zì radical

- the dictionary's definition of the characters, and

- an English translation of this definition

– Looking ahead:

30. Prepare some notes and ideas for your term paper.

Make a list of possible observations and, for each observation, one or more research questions.

Please bring your notes to class for discussion.

You can read more on the relevance (and art) of observation here.

...and the encore

31. What is this?

FYI

CHILL! | CHInese Linguistics in Leiden

“Chinese taboo characters and passive constructions as heuristic tools: Redating the Messiah Sutra 序聽迷詩所經 and On One God 一神論”

A lecture by Sun Jianqiang

The Messiah Sutra and On One God are two Chinese manuscripts that are taken as the earliest statements of the Christian faith in China. According to the conventional understanding, they were created by the first known Christian missionary Āluóběn 阿羅本 around the 640s.

In this talk I will show that, relying on the name taboo tradition and the use of the bèi 被 passive construction, one can make the case that the two texts were created most likely no earlier than the period of the late Tang and Five dynasties (800-960).

These results have consequences for the traditional narrative of Christianity in pre-12th-century China.

Place: Van Wijkplaats 2 / 006

Time: Wed 7 March, 3:15-4:30pm

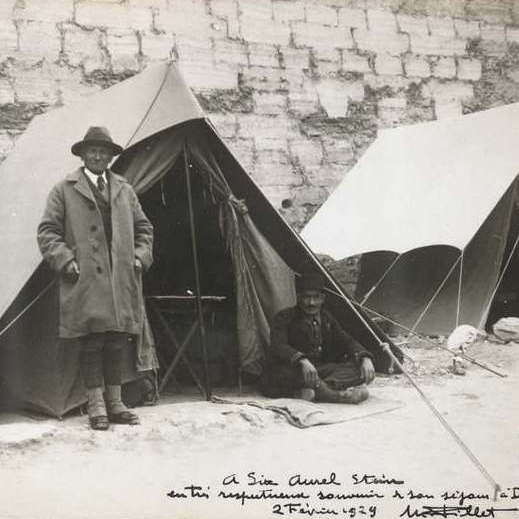

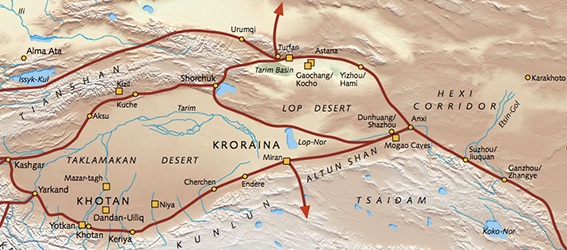

| "By far the largest corpus of early Chinese manuscripts available to us today is the huge cache found by Sir Aurel Stein and others at Dunhuang in far western China in the early years of the twentieth century." Peter Kornicki, "Bluffing your way in Chinese" (2008: 2) |

Diamonds from Sand City: Dūnhuáng's linguistic treasures

Since times immemorial, the desert trails connecting India with China were busily travelled by merchants and monks, artists and adventurers.

This week, we zoom in on the oasis town of Dūnhuáng 敦煌, a.k.a. 沙州 Shāzhōu 'Sand City', whose Mògāo 莫高 caves has been a Unesco World Heritage Site since 1987.

One of the first scholars who realized that this site harbored a priceless linguistic time capsule was the Hungarian-born Briton Stein Márk Aurél, later Sir Marc Aurel Stein (1862-1943).

Initially attracted to Dūnhuáng by its Buddhist art, Stein chanced upon a cave full of manuscripts and prints in 1907. Today, the study of Dūnhuáng documents remains a fascinating multi-disciplinary field.

Text and audio

Text and audio

Volume II, Texts

Volume IV, Plates

Aurel Stein, K.C.I.E., Serindia: Detailed report of explorations in Central Asia and westernmost China

Oxford: Clarendon, 1921.

Available in the Leiden University Library's Special Collections.

Due to their age, these two volumes are not accessible as "Course Reserve" items.

You need to got to the Special Collections Reading Room to consult these works. This reading room is on the same floor as the Asian Library, but two corridors across.

Special Collections are making these volumes available for students of this Sinographics course. Just show your library card at the desk and remind library staff that both volumes are reserved under my name.

Development notes: For future runs of this course

Sources to be considered

– Serindia:

– for Volume IV:

http://ishare.iask.sina.com.cn/f/19687838.html – Beginning to page III

http://ishare.iask.sina.com.cn/f/19723014.html – From page XLV to page LXXXIII

http://ishare.iask.sina.com.cn/f/19777383.html – From page to LXXXIV page XCII

http://ishare.iask.sina.com.cn/f/20302724.html – From page CXXXIII to page CLXXV

-

Whitfield (2009)

Susan Whitfield, "Stein's Silk Road legacy revisited".

In: Asian affairs, volume 40, no. 2, 2009, pp. 224-242.

Available as an online publication from the Leiden University Library.

-

Fāng (2014)

方廣錩 Fāng Guǎngchāng, "敦煌遺書數字化的現狀, 基本思路, 目前實踐及設想 / Status, basic concepts, current practice and tentative plan for the digitization of Dunhuang manuscripts"

Opening keynote lecture, 6 September 2014, of the "Prospects for the study of Dunhuang manuscripts: The next 20 years" Conference held at Princeton University.

(If you want, you can click "Download video" inside the web-player window to create a local copy of this lecture. Note, however, that the recording has audio only.)

Reading notes

Whitfield (2009):

32. The map shown on p. 225 is available online as a scalable color map from the British Library.

Background

Susan Whitfield, Aurel Stein on the Silk Road

London: British Museum Press, 2004.

Published at the occasion of the British Library exhibition "The silk road: Trade, travel, war and faith".

Includes a glossary.

Available in the Leiden Asian Library: see the Course Shelf dedicated to this course, number ALCOL17-60.

International Dunhuang Project, "Conservation of the Diamond Sutra".

Uploaded on Youtube on 27 May 2009.

Fascinating footage on the multi-disciplinary challenges of preserving the world's oldest dated printed text.

More video's from the IDP are available at their Youtube channel

Peter Kornicki, "Bluffing your way in Chinese".

Sandars Lectures in Bibliography,

Cambridge University Library, 11 March 2008.

"The problem of nomenclature"

In: Norman (1988) , pp. 135-138.

"Classification of Chinese dialects"

In: Norman (1988), pp. 181-183.

Assignments

32. Backlog items

Wenjing: Second call for your hand-in assignment #1 – this Friday, 23 Feb 18, at 1:00pm.

Please note the format requirements for written assignments.

33. Individual items

Aurelia: Stein's Volume II: Text notices that the sutra scroll was "in excellent preservation and complete".

Elaborate conservation was undertaken in the years 2003-2010, as shown in a British Library video on the Conservation of the Diamond Sutra.

Now, compare Stein's original picture with the photo taken at the British Museum in the mid-1970s.

Can you point out what type(s) of restoration or conservation work had been performed by that time?

Biyue: Aurel Stein was not only a trained philologist, but also a skilled archeologist, "recognizing the importance of careful excavation, of stratigraphy and of recording each find's location" (Whitfield 2004: 18).

In two or three sentences, describe the technique of stratigraphy. When did this technique originate?

Bodi: See assignment #27: please present four blanks of your choice in the last column.

Iris: There is a short Chinese text preceding the translation of the Diamond Sutra itself.

What does the first line say?

Jiayun: See assignment #27: please check if you would like to add any items in the first column.

Lili: Among the Dunhuang manuscripts, there are detailed drawings of hands held in many different positions.

(a) Find one of these drawings in Stein's Volume IV: Plates.

(b) Do they depict hand positions or hand gestures? What was the purpose of such drawings?

Nick: What is the Chinese term for 'archeology'? And what does it literally mean – morpheme by morpheme?

Rick: See assignment #27: please present four blanks of your choice in the last column.

Wenjing: See assignment #27: please check if you would like to add any items in the first column.

34. Read Whitfield (2009) and bring your reading notes to class.

We will discuss your questions and remarks on a page-by-page basis.

35. Make a list of all language names mentioned in this text, restricting yourself to languages spoken natively in the areas explored by Stein.

For each of these languages, look up their genetic affiliation (language family, subgroup, branch etc).

For some assistance, try the Linguistic Toolbox at the bottom of this page.

36. Listen to Fāng's (2014) keynote speech and bring your listening notes to class.

37. In two or three sentences, summarize what Fāng considers to be the major challenge(s) for the digitization of Dunhuang manuscripts today.

38. Two volumes of Aurel Stein's original work of 1921 are available in the Special Collections Reading Room.

First, have a good look at these works.

In Volume IV: Plates, check that you understand the page numbering system.

On page C of Volume IV: Plates, find the photo of the "printed roll" at the lower half of the page;

on the same page, find Stein's inventory number for this item;

and in Volume II: Text, under the same inventory number, find Stein's detailed description of the item.

Now, establish whether Stein himself realized the historical significance of this particular scroll.

39. The International Dunhuang Project (IDP) has uploaded a high-resolution image of the same scroll, which contains the full Chinese text of the Diamond Sutra.

This webpage includes a digital facsimile edition of the scroll, along with a full English translation of the sutra.

Sanskrit title: वज्रच्छेदिकाप्रज्ञापारमितासूत्र Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra

Chinese title: 金剛般若波羅蜜多經 Jīngāng Bōrěbōluómìduō Jīng (note the Mandarin readings for 般 and 若), abbreviated to 金剛經 Jīngāng Jīng

English title: Diamond-Cutter-of-Perfect-Wisdom Sutra, abbreviated to Diamond Sutra

On the IDP page, if you click on "NEXT IMAGE" once,

you will have reached the last line of the printed text, indicating its date of publication. (to see more details, click "LARGE IMAGE")

This line of text is lacking in the IDP translation, but you will find an English translation in the short but useful introduction to the Diamond Sutra by the Silkroad Foundation.

(a) Correct the Silkroad Foundation's English translation of the Chinese date.

(b) Find the name of the emperor ruling the Táng 唐 at the time of publication of this scroll.

(c) Use the Chinese-Western calendar converter provided by the Academia Sinica, Taiwan, to check if the Julian date give by the Silkroad Foundation is correct.

(d) Check if you can tell on what day of the Julian week this Chinese edition of the Diamond Sutra was published.

...and the encore

40. Chinese-Language-Names Recap:

First, check that you understand what is meant by each of the language names in the list below.

Some nomenclature is explained in section 6.2 in the assigned chapter from Norman (1988).

For additional treatment, see Table 1.2 "Chinese language names" in:

Jeroen Wiedenhof, A grammar of Mandarin (Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2015), p. 8.

Available from the Asian Library reference shelves, PL1107 .W54 2015.

Now arrange these terms in meaningful patterns: geographically, chronologically, according to domain, or otherwise.

- Ancient Chinese

- Archaic Chinese

- Báihuà

- Běifāng Fāngyán

- Chinese

- Cantonese

- Early Mandarin

- Early Middle Chinese

- Formosan languages

- Gàn

- Guānhuà

- Guóyǔ

- Hakka

- Hànyǔ

- Hokkien

- Huáyǔ

- Kèjiā

- Late Middle Chinese

- Mandarin

- Middle Chinese

- Mǐn

- Modern Chinese

- Northern Guānhuà

- Old Chinese

- Pǔtōnghuà

- Southern Guānhuà

- Taiwan Mandarin

- Taiwanese

- Wú

- Xiàndài Hànyǔ

- Xiāng

- Yuè

- Zhōngguóhuà

- Zhōngwén

FYI

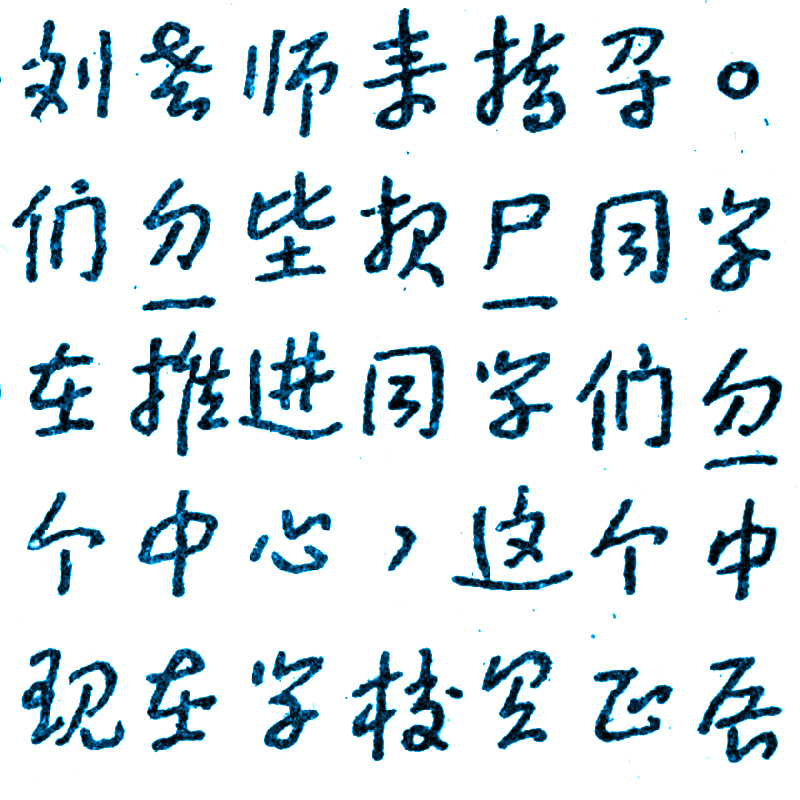

Moderne Chinese handschriften

Crash course (in Dutch) | Reading contemporary Chinese handwriting

Catching up and looking ahead: Linguistic approaches to sinographics

Over this first semester's block, we have been tackling an abundance of subjects from many different angles. This calls for a moment of reflection; remember that reflection is one of the most powerful instruments in the toolbox of science.

This week, therefore, we will cover some backlog from Week 1 to Week 5, as well as discuss any outstanding issues from these sessions which you may wish to raise.

We will also be look ahead to the the tasks before us, first and foremost about the subjects of your term papers.

Texts

-

Writing on language

See <writing_on_language.htm>

-

Murphy Paul (2016)

Annie Murphy Paul, "How to increase your powers of observation".

Time, 2 May 2016

Assignments

41. Backlog items

- Biyue, Bodi, Zhenlin: Make sure to have a good look at Stein's (1921) Volume II and Volume IV.

For each of these two volumes, write down one linguistic statement about a historical script illustrated or discussed in these works.

In other words: in both cases, the subject of your statement should be a script or script sample mentioned by Stein (please note down where: chapter & page number!), and the nature your statement must be linguistic.

Keep it short and simple! One sentence per statement.

Deadline: Friday, 9 March, at 1:00pm. Please note the format requirements for written assignments.

- Jeroen: Check contents & lay-out of the

edition on the Course Reserve shelves in the Asian Library.

42. Read "Writing on language" and bring your reading notes.

We will discuss your questions and remarks in class.

43. Read Murphy Paul (2016) and bring your reading notes to class.

We will discuss your questions and remarks. (and observations ;-)

44. We are returning to the subject of your term papers.

In your notes, check my comments on your assignment #30, and be prepared to report on your progress so far.

Assignments heads-up

On Monday, 26 March (Block 4, Session 1: after the semester break), a first draft of your term paper will be expected.This draft will be assessed as Hand-in Assignment #2.

For general hints on linguistic writing, please consult Writing on language.

Two weeks later, on Monday, 9 April (Block 4, Session 3: after the Easter break), you will be expected to deliver a (very short!) oral report on the subject of your term paper.

This report will be assessed as your Oral presentation.

As announced, in order to help you plan ahead, you can prepare draft versions of your term paper at any time:

- I will return your work with my comments

- This list of proofreaders' marks may assist you in reading my comments

- In case you wish to discuss my comments, please make an appointment

Please allow two days between handing in any draft and your appointment.

45. See assignment #27:

- Please present blanks of your choice in the last column.

- Check if you would like to add any items in the first column.

- This time, this assignment is meant for all particiants, not just the four of you who brought their solutions last week.

- Whenever possible, please prepare your solutions digitally – so as to facilitate the presentation of your solutions on this webpage in the coming weeks.

...and the encore

46. What is this?

Block 4

Language and script (2): Chinese writing and writing Chinese

Welcome to Block 4!

As the final session in Block 3 was cut short by a career-market outing in The Hague, some house-cleaning duties have remained at the outset of this new Block.

Also, as announced: this week, it's assignment hand-in time again! Make sure to have your work ready and presentable, and to report any problems timely.

Texts

Texts

Wiedenhof (2015)

Jeroen Wiedenhof, "The transcription of Mandarin"

In: A grammar of Mandarin.

Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2015, pp. 414-428.

Wiedenhof (2005)

Jeroen Wiedenhof, "Purpose and effect in the transcription of Mandarin"

In:. 李哲賢 / Lee Jer-shiarn (ed. in chief), 2004 漢學研究國際學術研討會文集 [Proceedings of the International Conference on Chinese Studies 2004].

斗六 / Touliu: 雲林科技大學 / National Yunlin University of Science and Technology, pp. 387-402.

Assignments

Hand-in Assignment #2

Write a short first draft of your term paper. Hand it in, printed on paper, at the beginning of class on 26 March, or in my pigeonhole beforehand.

Please note the format format requirements.

- Maximum length: 2 sheets A4

- Please do not not write text about your paper, but text for your paper

Please keep the scope of this version restricted – you can always elaborate later.

Make sure you hand in at least two more draft versions during term.

The more versions you hand in, the more feedback you will get. For general hints on linguistic writing, see Writing on language.

My pigeonhole (at the Arsenaal building, first floor) is available for your (printed!) work at any time during term.

As mentioned in class: please feel free to discuss your plans and ideas, but do not wait until the last moment to make an appointment.

– "The transcription of Mandarin":

47. Read the text and bring your notes.

We will discuss your questions and remarks in class.

48. In your own words, describe the difference between Character Pinyin and Linguistic Pinyin.

49. The transcription dilemma mentioned at the bottom of p. 419 is also addressed in the "Purpose and effect" text, in Section 2.2.

Please summarize this dilemma in your own words, clearly distinguishing phonetical, phonological and transcription issues.

– "Purpose and effect":

50. Read the text and bring your notes.

We will discuss your questions and remarks in class.

51. Section 2.1 mentions a modern (20th-century) instance of linguistic change in spoken Mandarin that is frequently overlooked.

In one or two sentences, write down how this situation came about.

– Remaining from Block 3, Week 6:

(45). See assignment #27:

- Please present blanks of your choice in the last column.

- Check if you would like to add any items in the first column.

- This time, this assignment is meant for all particiants, not just the four of you who brought their solutions last week.

- Whenever possible, please prepare your solutions digitally – so as to facilitate the presentation of your solutions on this webpage in the coming weeks.

FYI

FYI

Wénlín

As requested by some of you, here is some information on the Wénlín software suite:

"Wenlin Software for Learning Chinese integrates a variety of tools for instant-access to more than 300,000 Chinese-English entries, 73,000 Chinese character entries, 62,000 English-Chinese entries, and 11,000 Seal Script entries.

Wenlin’s versatile and easy-to-use interface tackles the most frustrating obstacles for students, scholars, and speakers of Chinese.

Wenlin’s integrated solution runs on a variety of computer platforms (including Mac and Windows), and includes expandable Chinese dictionaries, a full-featured Unicode text editor, a flashcard system, pronunciation recordings, handwriting recognition, and much more."

For more information see the Wenlin Institute products page.

Marmite update

As we saw, early European exploration in China was supported by developments in food technology.

A century later, the fate of Marmite serves to symbolize cross-channel differences:

"Going Dutch" (in Dutch)

No class today

Easter Monday

Term-paper presentations

Today's session will consist of two parts:

Assignment

Oral Presentation

On 9 April, as announced, a very short oral presentation will be expected of you about the subject of your term paper.

Points of consideration:

- Your presentation will be in English

- Maximum duration is five minutes – please time yourself in preparation!

- Your target audience intelligent and interested, but not necessarily trained in linguistics or in Chinese. Fellow students from other departments may be invited to listen in.

- A short handout for the audience will come in handy, because it will save you time writing on the blackboard: please prepare 9 copies

- Powerpoints are allowed, but only after prior consulation (over email) – also note that setting up your system will cut into your five minutes!

Brushes with power: Script and society

Today's session will continue were we left off last week

Oral presentations:

Eight five-minute overviews, each introducing ongoing work on one term paper.- Discussion of this week's text:

Facts from the fifties which decided the Chinese script's destiny.

Texts

Kraus (1991)

"The failed assault on Chinese characters"

In: Richard Kurt Kraus, Brushes with power.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991, pp. 75-82.

Wiedenhof (2015)

"Features of the Chinese script"

In: Jeroen Wiedenhof, A grammar of Mandarin.

Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2015,

§ 12.3, pp. 365-384. [12 Apr 18: added questions on this text, see below]

Assignments

52. Read both texts and bring your notes.

We will discuss your questions and remarks in class.

– "The failed assault on Chinese characters"

53. On p. 75 of Kraus' text, he notes the Korean use of "a more clearly phonetic" script instead of characters.

a. What is the name of this script? How and when did it come into being?

b. How "clearly phonetic" is it?

c. If the Chinese script is not "clearly phonetic", then how could it best be characterized?

54. Kraus' chapter repeatedly mentions John DeFrancis' work.

a. If you are not familiar with John DeFrancis' name:

do look up some details about his life and work.

b. On p. 78, Kraus states that "DeFrancis points out that..." without quoting a source.

Can you trace this citation?

c. Kraus paraphrases DeFrancis' statement that in the 1950s, "no one in China was willing to appear to challenge Stalin on this point".

On what point, exactly?

55. P. 81 shows a woodcut from a 1958 issue of the journal 中国妇女 Zhōngguó Fùnǚ "Women of China".

a. Can you identify the characters in this illustration?

b. Can you translate them? (

A friendly reminder: prepare all your answers in writing)

56. On p. 82, Kraus mentions a childhood memory from Chinese opera singer 新凤霞 Xīn Fèngxiá (1927-1998) featuring a "discarded cap of a fountain pen".

a. When and where were fountain pens invented? What writing tool(s) where they meant to replace or supplement?

b. When were they first used in China? What writing tool(s) did they replace, or supplement?

– "Features of the Chinese script"

57. The first paragraph of p. 365 describes what characters "consist of".

What consequences can this phrase "consist of" have in terms of linguistic methodology?

58. For each of the stroke-order principles in Table 12.5, try to find at least one exception.

59. For native speakers of Mandarin:

in Table 12.10, compare these letter names with your own pronunciation, and note down any differences.

60. In Table 12.11, can you think of punctuation marks which are missing?

61. At the bottom of page 371, what do the slashes transcribe in "the sound /s/"?

Can you write these three examples – cent, sent and scent – using the same transcription?

62. At the bottom of p. 372, please comment on the English translation "A book from the sky".

63. The small text of p. 375, mentions a "danger of circularity".

Please formulate this danger in two or three sentences of your own.

64. Some historical aspects of the character 年 are mentioned on p. 377.

What linguistic terminology is available to describe the relationship between 'millet', 'harvest' and 'year' discussed here?

65. Section 12.3.3 discusses the 六書 liù shū 'Six Categories of the Script'.

In his 2009 "Ludic writing" article, Wolfgang Behr proposes a highly original model for the analysis of the relationship written characters and linguistic signs.

This model, in his words (2009: 291)

"allows us to identify certain character structures beyond the coverage by the traditional “six scripts” (liùshū 六書) theory of the Hàn dynasty, [...] whose inadequacies have long been noted and discussed."

Can you give concrete examples (quoting individual characters) of such "inadequacies"?

66. Table 12.14 illustrates the large propertion of infrequent characters.

Can you identify one or more social factors which have contributed to the survival of infrequent characters?

Development notes: For future runs of this course

Assignment to be considered

– "Features of the Chinese script"

Which early dictionary seems to be missing in Table 12.13?

Language and script (3): Documenting Chinese

In last week's session, we looked at 20th-century reforms and standardization, both in the spoken and in the written domain.

Throughout history, these two domains, language and script, have often been treated as indistinguishable: not just in the public eye, but also in learned treatments and official policies.

A principled distinction between these two domains is the prerogative of linguistics. This week provides some background to the linguistic issues at hand in China at the dawn of the 20th century.

Text

Text

Coblin (2000)

W. South Coblin, "A brief history of Mandarin"

In: Journal of the American Oriental Society

Volume 120, no. 4, 2000, pp. 537-552.

Available online at the Leiden University Library.

Background

Background

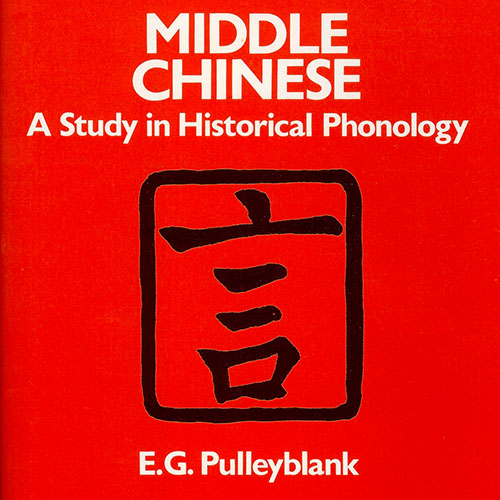

Pulleyblank (1984)

"The history of 'standard Chinese' "

"The phonology of Pekingese"

In: Edwin Pulleyblank, Middle Chinese

Vancouver: Universiy of British Columbia Press, 1984.

- "The history of 'standard Chinese'" = pp. 1-4

- "The evidence for Old Chinese" = Chapter 2, pp. 41-59

Available from the Asian Library, on the linguistics handbooks shelves.

Assignments

Left over from last week:

– "Features of the Chinese script"

Assignments 60 to 66

67. Check your progress with the term paper, and bring any questions to class.

– "A brief history of Mandarin"

As always, prepare your answers to all questions & assignments in writing.

Page numbers followed by a slash and the letter L or R (e.g. "p. 537/L") indicate the left or right column on the page.

68. Read both texts and bring your notes.

We will discuss your questions and remarks in class.

69. Be sure to identify and look up linguistic terms as well as historical names & events you are unfamiliar with

– and/or to brush up your knowledge on these items.

70. Provide your own English translations for each of the book titles mentioned on p. 537/R.

In the remainder of the article, keep checking that you understand the titles of all works discussed.

71. As mentioned in Four tones (Middle Chinese), the 入 rù tone (p. 538/L) is labeled as "entering or checked" in English.

a. Please check the etymology of the Chinese term.

b. Can you guess how the English labels originated?

72. Please summarize the conclusion at the bottom of p. 538/R in your own words.

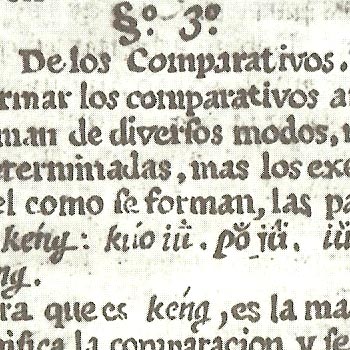

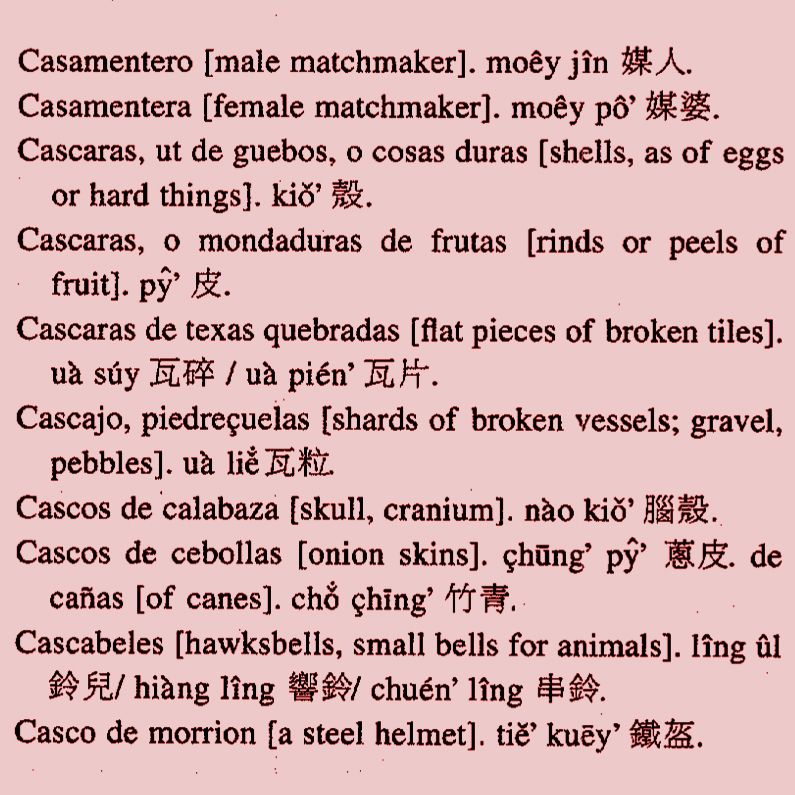

73. On p. 540/L, the Arte de la lengua mandarina and Vocabulario de la lengua mandarina by Francisco Varo are mentioned.

Check if modern editions of both these works are available – and if so, who are the editor(s).

74. On p. 542/R, it is explained that "the zhèngyīn system of ca. 1450 was based not on the pronunciation of a single dialect or area but was instead a composite entity".

a. What could be the reason that a purported linguistic standard is in fact composite in nature?

b. Cite both advantages and drawbacks of a standard of this nature for its speakers;

and for linguists of later generations.

c. Can you cite other (historical and/or modern) examples of composite linguistic standards in China?

75. As noted on p. 543/L, Jiǎng Shàoyú 蔣紹愚 has pointed out that for historical stages of Chinese, "spoken material has [...] been accessible only indirectly through the medium of the literary sources".

a. Please paraphrase this statement in your own words, and/or give an example.

b. Compare this state of affairs with the status of spoken materials in the description of the modern standard language as it arose in the twentieth century.

What sources for spoken Mandarin were linguists using in, say, the 1950s?

76. In the short abstract of this article (p. 537), it is explained that the text exposes a "flawed" view about the provenance of standard Mandarin.

a. Is there a difference in meaning between the terms

standard Mandarin as used here ("in its oldest sense", p. 537/L);

standard Chinese as used by Pulleyblank (1984: 1); and

Modern Chinese?

If so: please indicate the difference(s).

And if not: check if these terms differ in other way (e.g. style, user base, varieties of English)?

In linguistics as in any other branch of scientific research, flawed views are problematic only inasfar they cannot be falsified; otherwise, their very falsification helps science progress.

b. Give examples of flawed views in the field of language reconstruction (not necessarily Chinese) which have since been falsified.

c. Give examples of views in linguistics which cannot be falsified.

Bones to bytes: The digital revolution

As we have seen, the earliest extant specimens of Chinese writing are preserved in hard materials: bones, shells and bronze. Yet the character script was shaped for the longest time by soft and flexible materials: writing brush, paper and silk.

After the 10th century, new printing techniques created a boost in the transmission of science, literature and the arts. Movable type became cost-effective much later, after the steam engine allowed mechanization in the late 19th century.

In terms of material culture, the digital revolution is perhaps the most radical development in the history of the Chinese script, and of scripts generally. We will examine an overview and consider a number of special angles.

Texts

Texts

Wiedenhof (2015)

"The digital revolution"

In: Jeroen Wiedenhof, A grammar of Mandarin.

Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2015,

§ 12.5.2, pp. 402-406.

Apple (2017)

[Apple] Handwriting Recognition Team, "Real-time recognition of handwritten Chinese characters spanning a large inventory of 30,000 Characters"

Machine learning journal,

Volume 1, Issue 5, September 2017

Background

Background

Russell (2016)

"Signing off: Finnish schools phase out handwriting classes"

The guardian, 31 July 2015.

Hilburger (2016)

Christina Hilburger, "Character amnesia: An overview"

In: Victor H. Mair, ed., Sinitic language and script in East Asia: Past and present

Sino-Platonic papers, Number 264, December 2016, pp. 51-70.

Reading notes

–"The digital revolution"

77. The reference quoted here is Halpern and Kerman's "Pitfalls & Complexities" article, available from the CJK Dictionary Institute's website.

–"Real-time recognition"

78. In the introduction, if you wonder what "convolutional neural networks (CNNs)" are: don't worry, they will be illustrated in the next section.

Or if you can't wait: here's a clever introduction. And note the human angle: CNNs "take a biological inspiration from the visual cortex".

Assignments

Assignment heads-up

On Monday, 7 May (Block 4, Session 7), a near-final draft of your term paper will be expected.This draft will be assessed as Hand-in Assignment #3.

Left over from last week:

– "A brief history of Mandarin"

Assignments 74 to 76

This week's texts:

77. Read both texts and bring your notes.

We will discuss your questions and remarks in class.

– "The digital revolution"

78. As mentioned on p. 402, there are "persistent issues" in the conversion of characters between digital standards (compare the Reading Notes)

The notion of conversion, e.g. from 貝 to 贝, or vice versa, involves more than just a distinction. Conversion also denotes a degree of identity between the object and the result of the conversion. In this example, there is also a certain sameness between 貝 and 贝.

This leads us back to the linguistic leitmotiv of our course on scripts, and a consideration which will be relevant to many (if not all) of your term papers.

Whether we are linguists or not, the analyis of scripts requires a statement on the position allotted to language – "language" in the technically strict sense of the spoken (not the written) medium.

For this example:

a. Can we establish the degree of identity between 貝 and 贝 without reference to language? And between between 後 and 后?

b. How can we do this?

79. The character 与 "with a horizontal stroke crossing the downward hook, has increased in popularity within the Chinese script" (p. 403).

When you look at the previous sentence (i.e. here, on this webpage) is the horizontal stroke crossing the downward hook, yes or no?

80. The software illustrated in Figure 12.24 (p. 406) was referenced above.

The following is an experiment, not a contest.

a. Note down (strictly individually, and without consulting any dictionary) how many characters you know actively among the ten characters displayed in Figure 12.24.

Here, "actively" means that:

- you can pronounce the character's reading in one Sinitic language of your choice

- and you know a corresponding meaning, i.e. a meaning in that same language

We will compare the results statistically in class, comparing numbers between 0 and 10.

b. Write down at least three factors which may influence the result of this comparison.

– "Real-time recognition"

81. To which scientific domain(s) does this text belong?

82. The Introduction mentions the phrase "underlying character inventory".

The term underlying suggests a conversion, but this type of conversion differs from the one above.

In the context of the Apple article, what are the object and the result of the conversion?

83. In the section on "System configuration", we have a character of 48x48 pixels.

a. In terms of resolution, is this currently a realistic average? (–on screens? –in print? –in other domains?)

b. For fluent reading, what is the minimally required (square) resolution for Chinese characters?

84. In the same section, the number 30,000 is mentioned for

"one node per class, e.g., 3,755 for the Hànzì level-1 subset of GB2312-80, and close to 30,000 when scaled up to the full inventory"

The text that follows will mention "30,000 characters".

In your own words, what is the difference between 30,000 nodes per class and 30,000 characters?

85. The same number re-emerges in the title of the next section, "Scaling up to 30K characters".

a. What type of interests drove this feat of engineering?

b. How does the number of 30,000 compare to the numbers of characters usually addressed in educational, political and/or social domains?

86. The same section distinguishes a "character inventory" from "[r]endered fonts".

In your own words, what is the difference?

88. Imagine you are an aspiring sino-techie applying for a job in a software company.

Describe at least one specialist asset that you bring to the firm thanks to your training in the Humanities.

Development notes: For future runs of this course

Assignments to be considered

– "Real-time recognition"

##. Compare the headings of Figures 2, 3 and 4 with the first sentence below Figure 4.

What is the difference between "cursive" and "unconstrained" variants (i.e. "variations")?

##. Figures 7 presents "Similar shapes of U+738 (王) and U+4E94 (五)".

a. For the characters 王 and 五, can the corresponding handwritten forms be completely identical, or will these two always be distinguished?

b. If you do not know the answer to a., describe two different methods to solve this question (you do not need to actually perform these steps).

Outro / Evaluation and excursion

Outro / Evaluation and excursion

Today's session will consist of three parts:

- Final hand-in assignment:

as announced, a near-final draft of your term paper

- Student evaluation:

As part of the last session of the course, Leiden University organizes a formal student evaluation. This can be especially useful for newly created courses – as our seminar happens to be.

The evaluation process takes approximately 15 minutes. It is anonymous and confidential: see details.

Apart from this formal exercise, any comments and suggestions that you wish to share about the format and contents of this course are most welcome.

- Excursion:

The program is currently being finalized; details will be announced in class.

Just to be on the safe side: bring a raincoat!

![]() We meet in our usual classroom, and at the usual time.

We meet in our usual classroom, and at the usual time.

Assignments

Hand-in Assignment #3

Write a near-final draft of your term paper.

Hand it in, either in PDF or printed on paper, on or before Monday 7 May.

Please note the format format requirements.

FYI

FYI

Presentation on Chinese printing techniques

Marc Gilbert (Curator, Asian Library) and Jeroen Wiedenhof (LIAS/LUCL) present "Chinese karakters in druk: een eerste indruk" (in Dutch).

Brief intro on Chinese text-printing techniques, show of masterpieces from the Leiden collections, and a hands-on demonstration of an intriguing machine: the Chinese typewriter.

Day: Wedneday, 30 May 2018

Time: 2:00pm (without Leids kwartiertje)

Venue: University Library, Vossius room

If you want to join us: please register!

For details, see the University Library's announcement.

.jpg)